Smoke and Mirrors: How the Newly Declassified Drone Strike Guidelines Keep the Old System in Place

The Biden administration’s deceptive attempt to restructure an institution which cannot be reformed

The “new” restrictions for authorizing drone strikes overseas sound an awful lot like the old ones.

Early last month, the New York Times reported that the Biden White House declassified documents outlining the administration’s internal policy for conducting such attacks, following a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit by the paper. According to these documents, “US military and CIA drone operators generally must obtain advance permission from President Biden to target a suspected militant outside a conventional war zone, and they must have “near certainty” at the moment of any strike that civilians will not be injured, newly declassified rules show.”

According to the report, these rules were signed off on by President Biden in October. Aimed at minimizing civilian casualties, these guidelines stipulate that strikes should also be limited to situations in which it would be “infeasible” for the targeted individual to be captured via a raid. Because they’re nearly identical to the drone guidance issued by President Obama in 2013, the current restrictions the Times has unearthed aren’t worth the paper they’re written on.

This may seem like a step in the right direction – the number of people killed by drones since January 2021 is a small fraction of the totals during the previous two administrations – but this is only due to the fact that the nature of our foreign policy has shifted. We’ve progressed to the great power competition with Russia and China. We’re still occupying multiple countries in the Middle East but hostilities in these nations are nothing like they were a decade ago.

Because our objectives on the world stage have changed, we don’t use drones as much as we used to. However, we’ve still retained the right to rely on them whenever it suits us, as evidenced by the fact that the US military is bombing Somalia as we speak.

The rules currently guiding the Biden administration’s drone policy may seem like reform but have left the government’s drone program virtually unchanged.

**

On November 3, 2002, Qaed Salim Sinan al-Harethi was driving down a road outside of Sanaa. The US government identified him as being one of al-Qaeda’s top leaders in Yemen.

American forces weren’t deployed to the vicinity. They made no attempt to apprehend him in any way. Instead, the US military opted for a much simpler approach, choosing to incinerate al-Harethi with a CIA Predator drone with the push of a button. By all accounts, this is the first recorded strike of its kind outside Afghanistan.

It wasn’t long before these types of killings became a permanent part of the American arsenal, despite the fact that their legality, morality, and effectiveness were questioned from the very start.

al-Harethi was a member of al-Qaeda but had never been convicted of a crime in a US court of law. Proponents of strikes like these were quick to note that this was irrelevant. al-Harethi, they argued, was a soldier in the war against America and the US government had no choice but to tailor its understanding of legal norms to this new battlefield. This initial strike instantly made clear how ripe this new reality was for exploitation and abuse, and foreshadowed how quickly this system would spiral out of control.

When the US launched the Hellfire missile that killed al-Harethi, it also took the lives of five others that were traveling in the car with him. As reported by journalist Seymour Hersh at the time, there was no indication that US officials knew who was in the car with al-Harethi at the time of the strike. After news of the operation broke, the public was told that four of the individuals were members of the Aden-Abyan Islamic Army, a terror group with ties to the al-Qaeda network. The fifth was a man named Kamal Derwish, a 29-year with alleged ties to the bin Laden family, who’d grown up in Yemen and Saudi Arabia. According to the FBI, Derwish recruited American Muslims to attend al-Qaeda training camps.

Born in Buffalo, he was also an American citizen. The definition of who could potentially be subjected to this extrajudicial brand of justice began to widen from the very start of the so-called War on Terror. During the two years following the September 11th attacks, the US government circumvented the Constitution to reconfigure what was legal and what wasn’t. Executing an individual without trial – even an American citizen – was now permissible.

This new reality didn’t just affect the people we decided were [or potentially could be] terrorists.

The lion’s share of the impact of the American drone war was absorbed by those who found themselves near these individuals when we finally made the decision to strike.

The official tally from the Bush era tells us that the US military killed 296 terrorists as well as 195 civilians from 2001 to early 2009. Because how the government defines and categorizes casualties, we can say with certainty that these numbers are inaccurate; the former figure is unquestionably inflated, and the latter is absolutely just a fraction of the truth.

We will never know precisely how many civilians our drones have killed but this has never seemed to matter to the US government. Innocent people were dying, but the US military continued the drone program anyway. By the time he’d left office, President Bush had ordered at least 51 drone strikes, in Yemen, Somalia, and Pakistan.

The 2008 presidential campaign promised Hope and Change. In a way, it delivered.

Barack Obama was in fact different than his predecessor because he leaned on this brand of warfare much more, dramatically accelerating the use of drones during his presidency. The new commander-in-chief authorized two CIA drone strikes in northwest Pakistan – which killed as many as five children – on just his third day in office. He’d go on to launch more drone strikes during his first year in the Oval Office than Bush did during the previous eight.

On a Friday afternoon in 2016 – as the country was preparing for the long July 4th weekend – the Obama administration revealed the government’s drone statistics for the previous two terms.

This data set – released at a time when the White House knew few people would be paying attention – stated that the US had killed between 64 and 116 civilians in Libya, Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen, between 2009 and 2015. This total, instantly dismissed as being far too low by a number of organizations tracking airstrike casualties, was paired with another set of numbers. The administration said that between 2,372 and 2,581 “enemy combatants” were also killed by its drone program during this same time period.

As the now infamous 2012 New York Times article on President’s Obama “kill list” noted, all military-aged males in a strike zone would be classified as combatants “unless there is explicit intelligence posthumously proving them innocent.”

The laughable attempt at revision by his administration was an effort to conceal just how many innocent people were killed as a result of his orders.

One of the most egregious chapters of the drone war began with the September 2011 strike that killed Anwar al-Awlaki, a key figure within the al-Qaeda network.

A Department of Justice (DoJ) memo justifying the killing was released in June 2014 by a federal court, following a lawsuit by the New York Times and the ACLU.

“In the present circumstances, as we understand the facts, the US citizen in question has gone overseas and become part of the forces of an enemy with which the United States is engaged in an armed conflict; that person is engaged in continual planning and direction of attacks upon US persons from one of the enemy’s overseas bases of operations; the US government does not know precisely when such attacks will occur; and a capture operation would be infeasible,” the memo, penned by former DoJ official David Barron, noted. The US chose to assassinate an American citizen because capturing him would have been infeasible. Sound familiar?

Less than three weeks later, his 16-year-old son Abdulrahman, also a US citizen, was killed by yet another strike approved by Obama.

Confronted by the group We Are Change, senior Obama campaign adviser Robert Gibbs offered the following explanation for the child’s killing: “I would suggest that you should have a far more responsible father if they’re truly concerned about the wellbeing of their children. I don’t think becoming an al-Qaeda, jihadist terrorist is the best way to go about doing your business.”

According to the president’s former press secretary, the assassination of a child was permissible because of who his father was.

For the most part, mainstream criticism of these incidents was kept at bay by a compliant, obedient corporate press that rarely held the government’s feet to the fire on the drone program.

There was, however, just enough public pressure for the Obama administration to muster a response. This came in the form of its own set of guidelines for managing the US government’s transatlantic death machine.

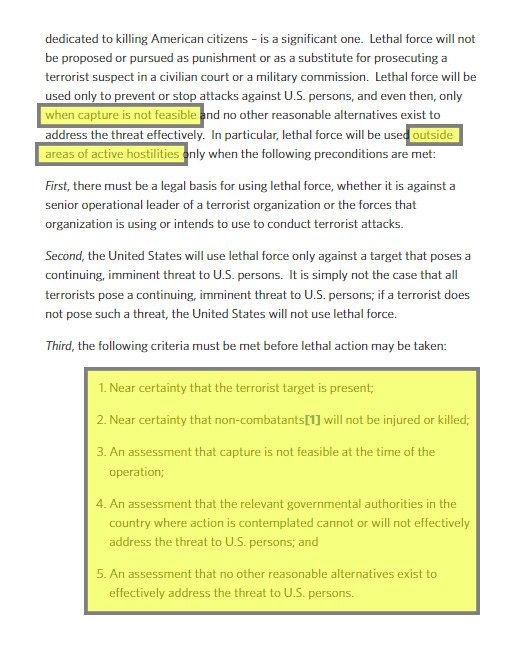

The image that follows contains one of the sections from this May 2013 White House press release.

These guidelines specify that they pertain to operations conducted “outside areas of active hostilities.”

This qualification was modified some three years later. On July 1, 2016, the same day the Obama administration released the grossly undercounted drone data cited above, the White House updated its guidance to note that their “best practices and procedures” for approving strikes would “be applied in future operations, regardless of the location.”

Because the “limitations” of these guidelines are mostly for show, it wouldn’t have really mattered if this decision had been reached sooner. However, it’s still interesting that it was announced 7 ½ years into Obama’s presidency.

It didn’t take long for it all to come full circle.

On Donald Trump’s ninth day in office, he ordered the execution of a military operation in Yemen. Military and intelligence officials told NBC News at the time that the raid’s primary goal was to capture or kill Qassim al-Rimi, a senior leader of al-Qaeda.

Carried out in coordination with the United Arab Emirates, the raid was said to have killed as many as 14 al-Qaeda fighters, up to 30 civilians, as well as US Navy Seal William Owens.

During his first address to a joint session of Congress, President Trump honored Owens – his wife, Carryn, had been invited to watch the speech from the First Lady’s box – but made no mention of the civilians that had been killed. His speechwriters also made the decision to omit any reference to eight-year-old Nawar al-Awlaki, who’d also died in the raid.

Her killing is an example of the endless similarities between the two parties that few in polite society care to acknowledge. Five years after Obama ordered the drone strike that murdered Anwar al-Awlaki’s son, Trump signed off on the strike that killed his daughter.

Despite all of the death and destruction Obama had caused, part of Trump’s political brand was built around the idea that his rival had actually not been brutal enough. Not too long after he became president, Trump shed the minimal restraints Obama had had in place. Now, senior military officials were given more freedom to authorize strikes.

In October 2020, Judge Edgardo Ramos of the Southern District of New York ordered the release of the 11-page document outlining the rules guiding drone strikes during the Trump administration.

According to a review by the Biden White House, exceptions to the requirement of “near certainty” that there would be no civilian casualties were frequently made throughout the Trump years. When civilian men were targeted, a lower standard of “reasonable certainty” was at times permitted.

The results were devastating. According to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a UK-based think tank, the US launched 2,243 drones during the first two years of Trump’s presidency. This compares with 1,878 strikes during all eight of Obama’s years in office.

Which brings us to Joe Biden.

It’s not just that the guidelines outlined by this White House track so closely with those released during the Obama administration. The specifics – a window into the criminal nature of the drone program as a whole – are also very important to note.

According to the breakdown offered by the New York Times, the rules apply strictly to “conventional” war zones. The article, citing a senior administration official, noted that the government only considers Iraq and Syria to be countries that still fit this mold. This is madness.

As of this writing, 304 of the 373 lawmakers who voted on the bill to authorize military action against Saddam Hussein’s government in October 2002 have left office.

Despite years of drone strikes and occupation, US involvement in Syria has never been put to a vote.

From there, the guidelines zig-zag from meaningless half-measures to caveats that immediately render those half-measures completely worthless.

For example, these rules stipulate that President Biden has discontinued the use of signature strikes, which target groups of suspected militants, a tactic that’s killed an unknown number of innocent people over the years. Because the casualty rate stemming from these strikes has been so high, the US government has committed not to use them… except, of course, when it wants to. The Times details the exception in the very next paragraph, writing that “exempted from the special procedures are strikes carried out in defense of American forces stationed abroad or in the “collective self-defense” of partner forces trained and equipped by the United States.”

That line of reasoning means that the rules don’t apply to Somalia, where US forces have been aiding Mogadishu-based government forces battling al-Shabaab for more than a year. It’s here where the overwhelming majority of drone strikes during the Biden era have taken place. [No, Congress never voted to authorize this intervention either].

Just last week, the Pentagon announced yet another strike in Somalia. US Africa Command told empire stenographer Natasha Bertrand what to write and she happily complied, as the screengrab from CNN’s update shows.

The word “initial” is doing a lot of heavy lifting in this article. We don’t think we’ve killed any civilians but, as always, we have no idea.

In the July article, the Times also reported that the Biden White House has not been completely transparent about the “new” guidelines it’s been using and has chosen to redact some of the rules that have been released. One of the redactions concerns a key aspect of the Trump guidelines that the Biden team supposedly took issue with.

“Also left censored was the standard of confidence an operator must have that a person Mr. Biden approves for killing is the same person in the operator’s target sights. However, the length of the redaction strongly suggests that the omitted words are “reasonable certainty,” one level down from “near certainty,”” the Times article noted.

To recap, the Biden administration has decided to leave its longstanding drone policy in place in all of the theaters it’s still operating in. The US also hasn’t terminated the practice in the countries in which operations have mostly or entirely ended, it’s just made the process a tad more bureaucratic. In essence, the US government’s self-imposed freedom to murder anyone it pleases, in any corner of the world, has been left unchanged. These so-called “limitations” are really anything but because the White House and the Pentagon can opt to ignore them at any time, without fear of legal or political consequence.

President Biden has drastically reduced the number of drone strikes but he hasn’t eliminated them.

What is also noteworthy about the drone program is how responsibility for these strikes is allocated. When a prominent terror leader is “taken off the battlefield,” a meticulously scripted press conference and an obligatory victory lap follow.

White House speechwriters make sure to pepper the president’s remarks with the word “I” to ensure that nobody misses that the commander-in-chief is the individual responsible. In the very rare instance that the drone program works in the way it was intended, the results are attributed to the president’s shrewd judgment as a leader, and promptly added to his list of accomplishments in office.

The overwhelming majority of the other strikes, which miss their targets and murder innocent people, are treated very differently. Presidents and administration officials rarely acknowledge them and are never held accountable for the destruction they cause.

A century from now, articles like this New York Times piece will serve as relics of a society that will hopefully be incomprehensible to our descendants.